Sir Sikandar Hyat-Khan: Prejudice Examined, A Punjab Perspective:

Table of Contents Preface..................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction..........................................................................................................................................4 Pakistan Ka Bhula Basra Bani: A Case Study of Sikander Hyat-Khan.............................................14 Background of Sir Sikandar Hyat-Khan.............................................................................................16 The Agrarian Reforms of the Unionist Party under Sikandar’s Ministry and the Reaction of the Opposition Parties in the Punjab Politics............................................................................................16

All Punjab Zamindara Conference under Sikandar’s Ministry at Lyallpur........................................20 Sikandar’s Vision / Philosophy:..........................................................................................................21 The Future Destiny: Towards Independence from Great Britain........................................................23 Equal Voice and Founding of Pakistan................................................................................................34 Lahore Resolution & the Partition of India By: Saeed Ahmad Butt...................................................36 All-India Muslim Conference.............................................................................................................38 Lead-Up to Partition:...........................................................................................................................39

Map of Pre-Partition Punjab.

The above map shows the boundaries of Punjab, after the annexation of Delhi and surrounding districts until the establishment of NWFP as a separate province in 1901.

The above map shows the linguistic division of Punjab. The red area is New Delhi, separated from Punjab in 1911 and declared as the new capital of British India.

The above map shows the provinces of British India and also the areas covered by the Princely States. In addition to that it also shows the religious demographics of India. “Punjab Province ………... contained 34 Princely States, besides the areas directly administered by the British.”

This map shows the five administrative divisions of Punjab and respective religious composition, according to the census of 1941.

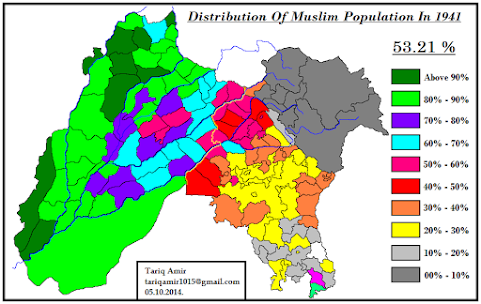

The above map shows the percentage of Muslim population of Punjab in Tehsils, according to the Census of 1941.

In the above map you can see the claims of the two parties. The red line shows the extent of Hindu/Sikh claim and the green line shows the extent of Muslim/Christian claim.

The above map show how much area and population both the parties eventually got. Sir Cyril Radcliffe Boundary Commission.

“While doing my research I noted many points that startled me, and I felt that the allegations of unfair award of the boundary commission and favoring India on this account, have solid grounds.”

1. Eight Muslim/Christian majority Tehsils that were contiguous to Pakistan were given to India, on the pretext of "other factors".

2. Not a single non Muslim majority Tehsil was given to Pakistan.

3. A large part of Kasur Tehsil was awarded to India on the flimsy ground of protecting Amritsar city.

4. Due to the above mentioned reasons, The State of Kapurthala, with a clear Muslim majority and surrounded by Muslim majority Tehsils, fell into India.

After doing all this research, collecting data and making maps, I kept on thinking that what should have been a more just and fair award? Or what would have been my decision? So I came up with the following map:

If I were to decide the partition, I would have allocated some additional areas, shaded in light blue. The basic rationale behind this proposal is to give Amritsar, being the holiest place for Sikhs, to India. While giving most of the Muslim majority areas to Pakistan, including some other areas in lieu of Muslim majority areas in Bist Doab. This additional territory I have marked with light blue color.”1

"Muslim Saints had attracted the local masses, irrespective of color, race, caste, and financial status and enabled them to understand the real Islamic message of humanity, fraternity, and simplicity. The Muslim Saints impressed upon the non-Muslims, particularly the downtrodden, oppressed, humiliated and neglected Hindus, and achieved huge conversions. Later on, the extremist behavior of Muslim orthodoxy caused shocking blows to Muslim rule in India."

A gap emerged in the religious sphere of Indian society particularly in The Punjab.2 Punjab was considered to be the key to the Indian Muslim politics not only by Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan and the leader of the All-India Muslim League (AIML) but also by the Congress hierarchy, the Sikh leadership and the British policy-makers in India and London. It was crystal clear in the speeches of Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah that the Punjab was the cornerstone of his Pakistan.

1 Tariq Amir 23 October, 2014. Doha – Qatar.

https://pakgeotagging.blogspot.com/2014/10/partition-of-punjab-in-1947.html Detailed Population analysis can be found at: https://pakgeotagging.blogspot.com/2014/12/muslim-population-of-india-according-to.html

2 Sikh Failure on the Partition of Punjab in 1947. Akhtar Hussain Sandhu.

Pakistan’s Creation depended on the Punjab. The region’s large Muslim population, agricultural wealth and even more importantly, its strategic position as the ‘land-gate’ of the Indo-Gangetic Plain made it crucial to the viability of a North Indian Muslim Homeland. Indeed, Jinnah called Punjab the ‘corner-stone’ of Pakistan. He, in his speeches and statements before and after the elections of 1945-46, declared that the key to the creation of Pakistan lay in the hands of the Punjab Muslims. The Congress and the Sikh leadership also thought that the Punjab held the key to the unity of India. It was perhaps the only Province which could have prevented the division of India and the creation of Pakistan. In Talbot’s words, "Pakistan’s creation depended on the Punjab."

Pakistan Ka Bhula Basra Bani: A Case Study of Sikander Hyat-Khan.

This article highlights various distinctive features of Sir Sikandar Hyat-Khan as a candid Statesman in Colonial Punjab. He possessed a great heart, accommodating political philosophy and steadfastness to resolve all sociopolitical problems diplomatically in the Punjab Province. This research paper aims at Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan as a unique Muslim Statesman who was above Communalism and his utmost efforts to create Communal Harmony in Socially Heterogeneous and Religiously diversified Punjab Province. Further, this article also analyzes Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan’s relations with the British Government and his efforts for inter-communal harmony, unity and to remove political differences among the Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs. Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan, as a Premier of the Punjab Province, convened a ‘Unity Conference’, signed the ‘Sikandar-Jinnah Pact’ with the Muslim League and the ‘Sikandar-Baldev Pact’ with the Sikhs for Communal Harmony, aimed at Reconciliation and the Welfare of all Communities; the Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs. Thus, Sir Sikandar Hyat-Khan was a Loyal Son of the Soil, shrewd Politician and farsighted Statesman, other contenders for Leadership, particularly in the Punjab, stood nowhere in relationship to Sir Sikandar, the Soldier distinguished by his bravery in Battle, Captain of Industry wherein he ably ran many Industrial and Agricultural Ventures all over India, his astute Statesmanship in accommodating the Hindhu and Sikh Minorities in the Combined Punjab, despite the fact that he was in a position to form Government on his own having won a comfortable majority of Unionist Seats and his farsightedness in predicting the horrendous

consequences of abrupt Partition both for the Punjabis as well as the Muslims who were to be abandoned to the tender mercies of Hindhu Majority Rule without check and balance as well as his being the Only Muslim Leader to call for inclusion of Kashmir in the Zone for Muslim Majority in the West of India. Besides this, his Administrative Abilities, balancing Political skills, accommodating behavior with all Political Parties, Communities and Patriotic enthusiasm made him a unique Leader in the Punjab’s Politics. His sincere Statesmanship can be found in his Parliamentary style of Governance, Administrative competency and his being a staunch supporter of Communal conciliation as well as the Unity of his Beloved Punjab.

Sikandar Hyat-Khan believed in fair politics rather than the politics of blame, as he said: “Politics is a dirty game, but I try to play it as fairly as possible.”

Throughout Sikandar’s long political career, he did not believe to inspire the audience by playing with their emotions. The chief attribute in his speeches as well as in his personal character was sweet expression, direct approach to the problem and spirit of compromise. Unlike many other Parliamentarians, he did not get popularity on mere speeches. On the other hand, he enjoyed popularity in political circles by establishing a reputation for tolerance, liberal politics and sound common sense.

“The “United Punjab” was a beautiful picture of communal harmony and strong bonds of mutual cooperation and understanding amongst the various communities such as the Muslims, the Hindus and the Sikhs. Every community of the “United Punjab” used to participate in each other‟s social and religious ceremonies. They jointly spent their time and were very close to each other; even they participated in the wedding and burial ceremonies of every community and all had a deep association with one another’s sorrowful and euphoric moments.”1

Why did Sir Sikandar’s role remain so controversial in that era? If Punjab would not have been included then there would have been no Pakistan.

Punjab figures prominently in the History of the Pakistan Movement and illustrates also the crosscurrents in twentieth-century Muslim Politics. Sir Sikandar Hyat-Khan was one among those who played a very active role in Punjab Politics in the most turbulent period of its History.

No research has even been conducted on this aspect of the topic, whereas it is worth-discussing in order to understand the Political, Communal and Economic conditions of the Punjab which facilitated the Feudal Class to occupy Political Chambers.

A number of gaps in the history of the freedom movement need to be filled.

"Historically the Punjab may be considered the most important Province of India. It was here that the Aryans of Vedic times first made their home. It was here that the hymns of Rig Veda were first chanted. It was to this Province, at the great University of Taxila, that seekers after knowledge flocked from various parts of the world. The Scythians and Tartars and Persians had to measure swords with the sons of the Punjab in their attempts to penetrate into India."

The Muslims ruled over Punjab for Eight hundred years which came to an end in 1799 when Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Punjab and established the Sikh Empire.

The power of the Sikhs was shattered with the death of Ranjit Singh. Sikh rule damaged the Muslim status as the British soon took over rule from the Sikhs, the status of the Muslims was restored during the British rule and they possessed, as before the ‘Sikha Shahi’, vast lands in different parts, including Gujrat, Jhang and Attock. The Muslims supported the British against the Sikhs due to the derogatory treatment towards them under Sikh rule and political instability in the region.

The Punjab had been annexed by the British from the Sikhs in 1849. This event followed a Century of turbulence that saw the collapse of the Mughal Empire, a period of semi-anarchy during

1 The Sikh Community in the “United Punjab”: Sikandar's Premiership and his Reconciliatory Policy.

Maqbool Ahmad Awan.

which confederacies, based on peasant caste and tribal alignments, fought for territorial control, and a feudal reaction within the warbands that resulted in the establishment of a number of petty princely states.

British rule brought stability to the Punjab. Ruling groups, if they desisted from provocation against British interests, were not replaced but confirmed as useful intermediaries between the State and the people. This partnership was consolidated with the Punjabis’ vital intervention on the side of the British in the armed struggle of 1857-1858. The Punjabis went on to contribute man-power and logistic support for Imperialism’s conflicts on the Northwest Frontier, and also helped Britain to conquer and police far-flung overseas territories. Such cooperation continued throughout the period of Imperialist rule, and with it the military became an important source of employment for Punjabis. About half the British Indian army came to be recruited from the Punjab; the British were fond of calling the people of this Province "the Martial Races of India."

The Punjab, with 56 percent Muslim population, supplied 54 percent of the total combatant troops in the Indian army.

Background of Sir Sikandar Hyat-Khan.

Sikander Hyat-Khan was born on June 5th, 1892 at Multan, in western Punjab. He belonged to the highly connected family of landed aristocrats whose members were often styled as Sardars and Nawabs for twenty-three generations descended from Sultan Mahmud Ghaznvi. His father, a topic for a novel unto himself, Nawab Sardar Mohammed Hyat-Khan was the first Muslim Indian appointed as an Assistant Commissioner, and later as a Divisional Judge and Sessions Judge in 1887 in the entire East India Empire.

His mothers family was equally aristocratic. Sikander Hyat-Khan’s mother came from a family of highly reputed administrators. She was the daughter of the Nizam of Kapurthala State. In addition, his other highly honored family members included his elder brother, the Prime Minister of Patiala Sir Liaquat Hyat-Khan, and his cousin Nawab Muzaffar Ali Khan, etc.

As a non-official, Sikandar gave ample proof of his leadership acumen. Through careful management and modern methods, at the age of 22, he turned his family estate of tea plantations at Palampur into a profitable concern. He acted as the non-official President of the Small Town Committee of Hasanabdal. Sikandar actively participated on the Board of Directors of eleven different corporations including three national Railway Companies.

Scaling new heights in rapid succession. In 1932, and again in 1934, Sir Sikandar acted as the first Muslim to govern Punjab since the rule of the last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. But he refused to move to the Government House, saying, I have no reason to, I have my own home. Already a Member of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire (MBE), he was promoted to be a Knight Commander of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 1933. Later that year, he received a Doctorate of Oriental Learning from The University of the Punjab.”1

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan. Volume No. 54, Issue No. 2 (July - December, 2017) Maqbool Ahmad Awan*

The Agrarian Reforms of the Unionist Party under Sikandar’s Ministry and the Reaction of the Opposition Parties in the Punjab Politics.

The Unionist Party was the first to cater for the needs of the rural population by extending the beneficent activities of the Government for rural and also well deserving backward areas of the Punjab

province. The schemes for rural development and elevation of the peasantry were the first initiative launched in the Punjab by the Unionist Party before any other province or political organization.

On assumption of office, Sikandar delivered his speech; he started by explaining his constraints and difficulties:2 “the Punjab Cabinet is under no delusion as the nature and extent of the limitations and restrictions which the Government of India Act imposed on the autonomy of the provincial sphere. Nevertheless, in pursuance of the clearly expressed wish of the electorate, it has undertaken the task of running the administration and securing the utmost good out of the new constitution”.3 According to him, in order to provide the requisite relief to the peasantry and remove the problem of unemployment, it would be necessary to explore fresh avenues and examine the existing sources of revenue with a view to augmenting the income to the extent which would enable them to take appreciable measures to mitigate the burden of the poor classes.4 After 1937, the first legislative move of the Unionist Party was the exclusion of clause from the Government of India Act of 1935, which defines the disqualification of honorary magistrates, sub-registrars and Zaildars from the election.5 The Punjab Premier Sir Sikandar also wanted to introduce reformative plans and reforms regarding the development and welfare of the province.

Sir Chhotu Ram and Sir Sikandar were well aware of the Party’s victory which was mostly based on the standing of its rural candidates and that only a third of those enfranchised had actually voted to the Unionists.6 They, therefore, sought to widen the circle of the Unionists‟ support by establishing a rural ‘Zamindar League Organization’ and supported to introduce the program of Agrarian Reforms.7 This stance was the establishment of the “Zamindara Raj” in the Punjab Province and they claimed that five out of six ministers were ‘Pucca’ or ‘Taqsali Zamindars’ (means the landowners of vast tracts of land) and also maintained a communal balance in the Cabinet.8 Sikandar Hyat continued to bring administrative, constructive and practical measures during his ministry after assuming the office as the Premier of the Punjab. He was quite eager to introduce the reforms for the welfare of the Punjabi community of the province.9 He also provided land grants in the Canal Colonies to his supporters (like his close ally Nawab Mehr Shah etc.).10 The Muslim League initially criticized Unionist Party for giving such grants exclusively as a reward for the political loyalty. In spite of this criticism by the rivals, the Unionists continued its policy agenda of decreasing the influence of the moneylenders. The Unionist Party allocated a large portion of budget within available resources to uplift the rural community.11 Nevertheless, it did not bring forward any radical step about Agrarian Reforms as these were unpleasant to its landed elite and Pirs’ supporters.12

The need for the Agrarian Reforms had been eagerly pushed by Sir Chhotu Ram whose experience in rural Punjab politics and deep influence amongst the Haryana ‘Jats Biradari’ was highly valued by Sir Sikandar.13 Sir Chhotu Ram was committed to grasp the chance provided by the Unionist Party in electoral success, for the implementation of the policies which he had been supporting for the last twenty years through his message in the columns of ‘Jat Gazette’.14 Sir Sikandar, although more vigilant than Sir Chhotu Ram, was also passionate and enthusiastic for the Agrarian Reforms.15

He believed that the major problems of the Punjab Province were Economic rather than Religious or Communal and the Unionists were capable enough to deal with these issues.16 Chhotu Ram devoted his career to uplift the Peasants “Social and Economic Status and to decrease the Moneylenders influence in the Punjab.”17 Sikandar Hyat, as mentioned earlier, vehemently believed in the Development of Rural Areas. Early in 1937, he advised the Unionist Ministers to launch a Six-Year Plan of Rural Development which allocated money for the betterment of Education and to establish Schools.18 The Agenda of Reforms was initiated in 1937-38, by the Punjab Premier, from the Platform of the Unionist Party, introduced a Six-Year Program for the Development of Remote Areas, Model Farms, establishment of Schools, Health Care Units, Advanced Sanitation and the Drainage System.19 In this regard, the Unionist Government passed many ‘Agrarian Bills’ in the mid of 1938, for the betterment of the Agriculturalists and for the benefit of massive Agrarian Population of the Punjab province.20 According to Ian Talbot, the Agrarian Program’s Centerpiece was provided by the Laws introduced during the 1938 summer session of the Punjab Assembly. As land reform was unpalatable to the Unionist Party‟s elite supporters, Chhotu Ram was again given his head in pursuing the moneylenders and traders.21 The Punjab Premier would have liked to table these measures much earlier, but due to the controversy over the Sikandar-Jinnah Pact in 1937, the matter was intentionally delayed.22 However, the Sikandar‟s Ministry passed a number of Acts to fulfill its promise of ‘lightening the burden of the peasantry and uplifting the backward classes’ through its agrarian program, firstly introduced as the ‘Agrarian Bills’.

The Agrarian Bills of the Unionist Party (The Golden Laws).

In fact, with the introduction of ‘Provincial Autonomy’, the ministry formed by the Unionists had comparatively more free hand to accomplish its task and pursue its Agrarian Reforms. The issue of debts was the top priority for the Unionist Party as it had been its main program and focal theme since its inception.23 These ‘Agrarian Bills’ were: I) ‘The Punjab Alienation of Land Second Amendment Bill’, (Act X of 1938) commonly known as the Benami Transactions Bill24 which empowered the Deputy Commissioner to declare all transactions null and void, if these were found to be in violation of the original Act.25 This bill was passed by the Assembly on 16th July 1938 and received the Governor‟s assent on 23rd February 1939; ii) ‘The Punjab Registration of Moneylenders Bill’26 (16th July 1938) was passed in order to establish effective control over the practice of money lending, by convincing moneylenders to get licenses and to curb the influence of moneylenders, and this bill came into effect from 15th June 1939;27 iii) ‘The Punjab Restitution of Mortgaged Lands Bill’ (21st July 1938) in order to terminate old mortgages of land (effected before June 8, 1901 and still subsisting) on payment of a reasonable compensation, when necessary by the mortgager to the mortgagee. These legislative ratification's attacked the moneylender’s position by closing the excuses in the Land Alienation Act of 1901;28 iv) ‘The Punjab Relief of Indebtedness Bill’; this bill determined the percentage of debts.29 It further provided that no decree or claim could be passed against an agriculturist debtor for any sum more than twice the original amount; v) ‘The Punjab Agricultural Markets Products Bill 1939’,30 popularly known as the ‘Mundi Act’ mainly intended to save the growers of agriculture‟s production from different malpractices of brokers and shopkeepers. This bill was passed by the Assembly on 2nd Feburary1939.31 Furthermore, the Unionist‟s Ministry took many steps to fulfill its promise to ease the burden of the poor cultivators and uplifting the peasantry classes. The ministry established ‘Debt Cancellation Boards’ at district level to reduce the burden of loans of the farmers and tenants. To establish these boards in all the districts which scaled down agriculturalists debts from 40 million to 15 million, the role of the Debt Conciliation Boards was also further streamlined by this Act.32 The Debt Conciliation Boards earlier came into existence under the ‘Punjab Relief of Indebtedness Act, 1935’, with such Boards being set up in each district. The objective of the Boards was to settle debts amicably and fairly. The new Act, however, had provided that if creditors failed to appear before these Boards or failed to prove their claims by their documents, the case of the creditors against the debtors was to be discharged.33 Besides, a provision in the Act added that if a creditor refused to accept the settlement decision of these Boards, he would not be able to claim any interest on the amount after the date of the decision of the Board.34 While these Boards provided much needed relief to the debt-ridden peasantry of the Punjab at the same time, they also enabled evasive and dishonest debtors to avoid paying genuine and fair creditors.35 The Act was an important legislative measure in the history of debt relief. Chhotu Ram, as usual, provided a lead in the forceful defense of its provisions.36 Sohan Singh Josh was among the strong opponents saying that most provisions of the Act were aimed to benefit the big farmers.37

The Unionist Ministry also issued a notification under Section 61 of the Civil Procedure Code which exempted the whole of the crop of an agriculturalist debtor and a proportion of the yield of his grain crop from attachment in the execution of civil decrees.38 As mentioned earlier, the Provincial Government was against dishonesty done under Benami transactions; ‘The Punjab Alienation of Land, Second Amendment Bill’ addressed that issue and therefore closed hitherto the loopholes created by the Benami transactions.39 This amendment not only plugged the loopholes in the 1900 Legislation, but made all the previous Benami transactions null and void.40 ‘The Punjab Restitution of Mortgaged Lands Bill’ also compelled the moneylenders to obtain licenses, to curb the influence of moneylenders and to control the business, it was like an accountability system in the Unionists Legislation's.41 The Sikh and the Hindu moneylenders claimed that it was just a cloak for the confiscation of their lands.42 They wanted to include the transactions relating to the agriculturalist moneylender classes which had been grown-up after the 1900 Act. However, this demand of the both communities was finally rejected. As a result, over 200,000 Sikhs and Hindus returned, and about 700,000 acres were transferred to their real owners.43 Sunder Singh Majithia echoed Chhotu Ram's words when describing the need to defend the cultivators from the Bania. The former, possessed lathi which could break all other lathis this was his behi (account book) and the lathi of the Zamindar is powerless to shield him from the lathi of Bania.44 Meanwhile, a conference was held by the Unionists at Lyallpur (Present Faisalabad), regarding above mentioned issues and to get a vote of confidence from the Masses and also the objective was to remove and resolve the conflicts and controversies among the Communities of the Province.

All Punjab Zamindara Conference under Sikandar’s Ministry at Lyallpur.

The Punjab‟s Premier, Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan arrived at Lyallpur along with Malik Khizr Hayat Tiwana and the other Unionist Ministers (Sikandar‟s Cabinet) on the evening of 3rd September, he reached there by train from Lahore. The crowded station of Lyallpur was decorated with Unionists Flags and Buntings.45 The Conference was organized by Sir Chhotu Ram and Sir Sikandar from the platform of the Unionist Party at Lyallpur, which was held in September 4, 1938, in which more than 150, 000 agriculturalists (including Kisan and Zamindars) expressed their support for these ‘Agrarian Bills’ which, later on, were called as the 'Golden Acts' or ‘Golden Laws’ and also as the ‘Golden Bills’.46 The Conference commenced shortly afterwards in a huge ‘Pandal’ which had been prepared on the ‘Dusehra’ ground at Lyallpur. Khizar Tiwana took his seat on the platform but this was very much Chhotu Ram's and Sikandar's show.47 They launched a spirited defense of the ‘Golden Bills’ before an audience of the Hindus, Muslims and Sikh Jats, which were nearly getting suffocated with the heat, despite the constant whirring of 200 electric fans.48 Sunder Singh Majithia severely rebuffed the charge that he was betraying his Sikh faith by upholding the interests of the Sikh cultivators against their non-Agriculturalist brethren.49 To gain credit and to popularize their Rural Party, the Punjab Premier himself and his ministers like Chhotu Ram and Mian Abdul Haye, made extensive tours of the province.50 Their speeches explained the benefits of these Legislations for the Peasants, who were mostly ignorant and illiterate.51

Punjab Premier, Sir Sikandar advised to establish a network of the Unionist branches which would create a locus of power independent of the Rural Chieftains. The trick was to work through them to found an Organization which might later be used to punch them into line.52 The task proved beyond him, although a beginning had been made in October 1937. The invitation to hold a Zamindara League

meeting at the residence of the Punjab Muslim League’s President Mian Iftikhar Hussain Mamdot at Mamdot Villa, Lahore, was in fact issued under the signature of Nawab Allah Bakhsh Tiwana.53 About two hundred prominent Landowners attended this meeting for the protection of the rights and interests of all Landowners, Peasants, Proprietors and Tenants in the Province.54 According to Ian Talbot, a patchy Organization was established during 1937-38. This was significantly strongest in the East Punjab where Chhotu Ram's populist style won support from the Jat Peasant Proprietors. The lack of progress elsewhere was a costly failure. A great opportunity was lost to institutionalize the popular support aroused by the ‘Ministry’s Agrarian Program’.55

The Premier asked the agriculturists not to fear anyone or to be affected by any agitation. He further added that “If anyone violates the laws in the Province, I will smash his head”.56 The significance of the bills lay in their effect on the prestige of the Unionist ministry which had successfully asserted itself, at least for the moment, as the upholder of the structure of local, and tribal political power in the rural Punjab.57 Indeed, if the Ministry had brought a revolution in the Punjab, it was a revolution that sought to sustain this agrarian structure in Punjab's rising "democratic" system.58 Even today, the old people remember nostalgically the revolutionary period’s enactments of new laws for the improvement of life in rural Punjab, for the emancipation of the peasantry from debt, for more protection against exploitation by traders, etc. The grand triumph of the Sikandar’s political shrewdness was the agricultural legislation which became popular during the introduction of ‘Golden Bills’. These ‘Golden Laws’ protected the peasants from the monopoly of the moneylenders. The next major development was the increasing of Muslim quota in the Government Jobs. In 1927, the percentage of the Government jobs was 40% for the Muslims, 40% for Hindus and 20% for Sikhs, while under the golden laws of the Unionists, which were passed in 1938, the percentage quota was increased for Muslims up to 50% for Hindus up to 30% and for Sikhs it remained at 20%.

Sikandar’s Vision / Philosophy:

Two things were uppermost in his mind during the last two or three years (of his life)and they were communal harmony and war efforts. He believed that his Motherland could not achieve autonomy without communal harmony and unless the country was made free from aggression by the victory of the United Nations (over the Axis Powers) which stood for freedom.59

The Unionist’s were a secular party with a mixture of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. Sikandar Hyat cooperated with the Muslim League but in public gatherings he condemned the partition scheme. But the question arises here Why Sir Sikandar's role was controversial in the Lahore Resolution of 1940?

The Unionists did their utmost to save above all that most important asset of the Punjab, its fertile land, ‘’dharti’’, and the tillers of the soil, ‘’zamindars’’, from ruin and utter destruction at the hands of usurers and money-lenders. It passed many ‘golden laws’ to save and salvage the peasants and their agrarian areas, so that these could go on being the bread-basket for all the Subcontinent and the nursery of future generations of honest and strong. men and women.60

The Hindus of India wished to revert to a Mythical ‘Maha Bharat’ Greater India of the period of Ashoka, the Sikhs were desirous of establishing a Homeland based upon the conquests of Raja Ranjeet Singh and the Muslims were forced to establish a State were Islam was Supreme although many Muslims were left stranded in India.

The partition of India was not viewed by many as the division of India into only two Hindu and Muslim states but there were strong opinions that India must be partitioned into more than two states, even though the cause of the Partition was definitely the two-Nation theory. Rahmat Ali, the famous originator of word Pakistan, referred to Bengal, Pakistan and Usmanistan as three independent states and suggested an alliance amongst them. Likewise, El Hamza, a Muslim writer, conceived of two predominantly Muslim areas in undivided India, one in the North-West and other in the North-East. Again Jamil-ud-Din Ahmed, a member of the All India Muslim League (AIML) and a lecturer in the Aligarh University, considered the recognition and fulfillment of the Muslim demand for two independent Muslim states in the North-Western and North-Eastern regions of India.61 Moreover there was a proposal of two Professors of the Aligarh University, Dr Syed Zafarul Hasan and Dr Afzal Qadri, for the division of British India into three Independent Sovereign States – two Muslim States of North-West India and Bengal, and one Hindu State. Then in 1939, Nawab Shah Nawaz of Mamdot, President of the Punjab ML published his Scheme for the division of India into five Countries, linked in a Confederation (Sayeed, 1960, p. 119), while Sir Abdullah Haroon proposed a division of India into two separate Federations. The Muslim Federation was to comprise the North-Western part of India and Kashmir only.

Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy, who was representing Bengal in the meeting of Subjects Committee, which was formed to draft the Lahore Resolution, opposed any idea of a separate homeland but argued that each of the Provinces in Muslim Majority areas should be accepted as Sovereign States and each Province should be given the right to choose its future Constitution or enter into a Commonwealth with a neighboring Province or Provinces.62 This view point of Suhrawardy and the initial draft of Sikandar Hyat, which suggested Dominion Status for Provinces and Defense, Foreign Relations and Communications for the Federal Government thus proposing a Confederation based on Maximum Provincial Autonomy, influenced the wordings of the Lahore Resolution so much that even after a number of modifications in the initial draft made by the Subjects Committee, the Resolution did not clearly demand one State for Muslims of the Sub-continent. Sikandar mentioned this in his speech in the Punjab Legislative Assembly on March 11, 1941 (Malik, 1985, p. 95).”63

The Passage of the 18th Amendment of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is a milestone and has resolved a long standing issue that had and was of serious consequence. This great service by the Pakistan People’s Party in general and Mian Reza Rabbani in particular, should get due importance and be recognized as such.

As a young man, Sikander Hyat-Khan served in both World War I and the Third Afghan War, becoming the highest ranked Indian to command a Company on Active Service, for which he was honored a Member of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire (MBE). After the War, he pursued a successful career in business and banking, while also becoming active in local politics as an elected official and member of the Unionist Party. On 2 January 1933, he was awarded Knighthood by the British Government and was promoted to be a Knight Commander of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire (KBE), the following notice from St. James’s Palace was published:

“The KING has been graciously pleased to give orders for the following promotions in, and appointments to, the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire: —To be a Knight Commander of the Civil Division of the said Most Excellent Order: Khan Bahadur Captain Sardar Sikandar Hyat-Khan, M.B.E., Member of the Executive Council of the Governor of the Punjab.”

The Future Destiny: Towards Independence from Great Britain.

Hyat-Khan’s work towards separation began early in his Political Career, when he was chosen to lead the Reforms Committee. The most salient examples of his efforts at achieving lasting Independence, however, are the Pamphlet, which he authored to address the constitutional problem, and his stance towards the War effort. In 1939, Hyat-Khan published The Outlines of a Scheme of Indian Federation, a document that offered a framework for Governance Transition and cemented his commitment to an evolutionary path towards Self-Rule. As Sir Reginald Coupland64 indicated, Hyat-Khan was only the second Muslim politician of any standing to take part in the constitutional discussion. The pamphlet contained, as Coupland reported:

“The sober and concise analysis of the existing situation with which he prefaced his proposals was in marked contrast with most previous Muslim publications. There is no reference to Hindu ‘atrocities’, no emotional appeals to Muslim sentiment, nothing about the Islamic World at large, no attacks on ‘British Imperialism’. The Constitutional problem is treated as a purely Indian problem which Indians can and must solve themselves.”65 Coupland also reports Hyat-Khan’s fervent belief that a Federation was not only desirable but indispensable, along with his commitment to achieving administrative control over the affairs of British India as quickly as possible following the end of World War II.66 According to his Zonal Scheme, an Indian Federation was to be comprised of Seven Zones with separate Legislatures. These would then make up an envisaged unicameral Federal Assembly of 375 members. In a letter written to Gilbert Laithwaite, Private Secretary of the Viceroy, on 29 June 1939, Hyat-Khan described his Federal Scheme and his belief that working with the British was in the best interest of the Subcontinent, as documented in Carter:

“The political salvation and safety of India depends on the British connection. If, God forbid, the link between Great Britain and India is severed or materially weakened, the Country will go to bits and revert to the chaotic conditions which it has witnessed in the past and eventually be enslaved by some other power. It is for this reason that, while I have suggested an immediate Declaration regarding the grant of Dominion Status, I have at the same time provided in my scheme a 20 years’ period of apprenticeship in such vital matters of Defense and External Affairs.”67

This is remarkably clear-cut evidence of the perceived need among Indian Leaders at the time to educate themselves to become competent Managers of their own affairs in due course.68 An evolutionary, peaceful transition of this sort may, however, could not have been popular at the time and unfairly contributed to suspicions that Hyat-Khan was a British Loyalist. However, from a historical perspective, his concerns were warranted and prescient. Hyat-Khan’s scheme was widely publicized and he advocated it until his death. During a meeting with Gandhi in July 1939, for instance, Hyat-Khan shared his Scheme. Gandhi’s confidence in Hyat-Khan’s approach is reflected in his response, mentioned by Pirzada:

“Dominion Status is a bitter pill for Congressmen to swallow and although the Scheme is too complicated to form an opinion, yours is the ONLY solution of a constructive character…I am glad that you have decided to publish it in full. I must thank you for taking me into confidence and asking me to give my opinion on it.”69

Hyat-Khan also pushed for this plan during a meeting with Winston Churchill in Cairo two years later. At the height of the War, while meeting with troops, Hyat-Khan pressed Churchill on the need for greater autonomy and Constitutional Reform of the kind he described in his Outlines. According to Hyat-Khan’s family, during the meeting, Churchill proposed a Monarchic Governance model to post-War Independent India, not unlike those proposed and instituted by Britain in the Middle East, in which Hyat-Khan would be King. Hyat-Khan declined, reaffirming his commitment to Democracy and to the Federation model of Governance detailed in his Outlines. (As a member of the Family, albeit much junior (born in 1954), this is the first I have heard of this. My impression was that that he (Sir Sikandar) was offered the Governor Generalship of All India.)

As Malik70 noted, this conversation with Churchill had a real impact. Perhaps nothing underscores Hyat-Khan’s commitment to Independence more than the reasons he broke with so many of his contemporaries and pushed for Indian support of the Allies during World War II. Hyat-Khan stood almost alone among notable Indian Leaders at the time in believing that India should enter the War against the Axis powers for a combination of philosophical, strategic and pragmatic reasons. Whereas most others, including Jinnah, and especially Gandhi and Nehru, saw it as the ‘white man’s war’, viewed Great Britain as an oppressor and for that reason opposed involvement in the War, Hyat-Khan’s strategy was different.71 He, too, saw Britain as an occupying force but opposed staying neutral, or siding with the Russians, Japanese or Germans, as some Indian Leaders had suggested, for several reasons. These included his philosophical commitment to stamping out the evil and oppression that was being pursued against a vulnerable religious minority by the Nazis. This was something that as a devout Muslim and someone who devoted his life to fighting sectarianism, made Hyat-Khan empathetic to the plight of the Jews. He also had strategic reasons for supporting the War. He was convinced that if India helped Britain, they would reward the Subcontinent with Independence. His conviction had historical precedence, since he himself had fought in World War I and following the War, Britain had taken steps to grant the Subcontinent more Autonomy. During World War I, 1.2 million Indian soldiers fought alongside the Allied powers and 72,000 lost their lives.72 In comparison, during World War II, two million Indian soldiers fought on behalf of Britain, with 89,000 casualties.73

Hyat-Khan stated at the time: “I believe that (the) valor and sacrifices of our fighting men alone can win India freedom just as they won [the] 1921 reforms by their sacrifices during (the) last War.” Hyat-Khan was also concerned that if Britain lost the War, British India would be open to invasion from forces in the East, West and Northwest, as well as chaos at Home. In a letter to Jinnah, dated 25 December 1941, Hyat-Khan wrote: “I have from the very outset of this War pleaded for a policy of wholehearted and unconditional support, because it is my fixed conviction that bringing this War to a successful conclusion is of vital importance to India and the Muslims throughout the World… by withholding our support at this critical juncture we will be jeopardizing the safety of our country…If, God forbid, the Nazis and Japanese succeed in this war all our political aspirations, and ambitions of a free and equal partnership, will be frustrated for good.” Hyat-Khan went on to critique Nehru’s approach, writing that while Nehru demands immediate declaration of complete Independence, he has not addressed how this will be achieved if the British lose this War. According to Hyat-Khan, in the same letter, Nehru was “banking on a victory of anti-Axis powers but without any help from the Political Party to which he belongs since it is wedded to a policy of non-violence.”

Ultimately, Hyat-Khan was successful in convincing a reluctant Jinnah and the Muslim League to support the War effort. In 1939, at the start of the War, the Indian Army had just over 200,000 troops. Under Hyat-Khan’s leadership by 1940, the Army’s size was increased to a million. In total, India supplied more than two million Army, Navy and Air Force combatants.74 The vast majority came from Hyat-Khan’s Province, the Punjab, and the Force quickly became the largest volunteer Force in the World at the time. A combination of Muslim, Hindu, Sikh and Christian Soldiers fought primarily in West Asia and North Africa on behalf of the Allies and against Nazism. It is a story not often told in the West that 89,000 of the more than 2 million Indian soldiers were killed in Battle.75

Hyat-Khan’s commitment to the War also reflected his understanding that once achieved, Independence must be sustained. This meant that the Subcontinent must not break away from Britain completely, until it had developed a robust economy and the capacity to defend itself from internal and external threats. In a speech in the Punjab Legislative Assembly on 11 March 1941, Hyat-Khan said: “We want Independence and Freedom…but we cannot become Independent merely by declaring that we are free … Unless we have strong, efficient and up-to-date Defense Forces our Independence will not be worth a day’s life.” Hyat-Khan saw the War effort as an opportunity to help Greater India develop Industry, skills and expertise, particularly in building an Economy and a Fighting Force capable of defending the Subcontinent. His point was well taken, as during the War a reported 14 million Indian laborers worked to keep the War Factories and Farms running. India provided 196.7 million tons of coal, 6 million tons of iron ore, 1.12 million tons of steel and 50 kinds of arms and ammunition. In addition, 35 per cent of India’s annual cotton textile production, amounting to about 5 billion yards, went into creating War material.

The fact that Hyat-Khan’s commitment to the War was intimately tied to his commitment to Independence partly explains why he reacted so strongly to Churchill’s statement regarding the Atlantic Charter.

2 The Tribune, 2 April 1937. Also cited by, Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 111-112 and Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 116.

3 Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 111.

4 Ibid., 111-112. Also see, Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana: the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India, 69.

5 Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj: 1849-1947, 116. For details, see The Punjab Legislators (Lahore: Punjab Provincial Assembly Secretariat, 1987), 1. Also see Daily Inqilab Lahore, March 11, 1939-1941and Mohinder Sing, History and Culture of Punjab, 205.

6 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana: Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India, 69.

7 Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 116 and Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 69.

8 See Mohinder Sing, History and Culture of Punjab, 206 and Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 109

and Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 69. Sikandar‟s Cabinet members were; Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, Malik Khizr Hayat Tiwana, Sir Chhotu Ram, Manohar Lal, Sunder Singh Majitihia and Mian Abdul Hayee. For details, see Lionel

Carter, Punjab Politics, 1940-1943: Strains of War, Governor’s Fortnightly Reports and other Key Documents (New Delhi: Manohar Publishers, 2005), Enclosure to no. 95.Government House, Lahore, January 11th, 1942. 290-291.

9 Ibid., 207.

10 Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 116.

11 Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 125 and Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 117.

12 Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 117.

13 Ibid., 117 and Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 110.

14 Ibid., 117.

15 Ibid., 117.

16 Ibid.,

17 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 81, see fn, no 27 and Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 117.

18 Lajpat Rai Nair, ed., Sikandar Hayat Khan: The Soldier-Statesman of the Punjab (Lahore: Institute of Current Affairs, 1943), 19 also see Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 71.

19 Ibid., 19. Also see, Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 117.

20 Ibid.

21 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 72.

22 For details, see David Gilmartin, Empire and lslam; Punjab and the Making of Pakistan (London: I.B. Taurus), 174-76 and S. Qalb-i-Abid, Muslim Politic, in the Punjab, & Punjab Politics: 1921-47 (Lahore: Vanguard publisher, 1992), 200-201.

23 Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 112.

24 Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 118. For details see, Punjab Government Gazette, 17th July 1939, 119.

25 Governor to Viceroy, 8 July 1938, L/P & J/5/238, IOR.

26 For details see, Punjab Legislative Assembly Debates, Vol.-V (Lahore: 1938), 123. Also quoted by, Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 84. For more details see, Punjab Government Gazette, 2nd September 1939, 111-114.

27 Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 118. For details see Punjab Government Gazette, part-1, 9 June 1945

28 M. A. Zaidi, Evolution of Muslim Political Thought in India, 162-166. Also see K.K Aziz, ed., The All India Muslim Conference, 1928-1935, A Documentary Record (Karachi: National Publishing House Ltd., 1972), 29. For further detail, see S. Qalb-i-Abid, Muslim Politics in the Punjab, 204-205 and Ian Talbot. Punjab and Raj, 117-118.

29 Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 118.

30 N. H. Mitra, ed., Indian Annual Register, Vol-II, 1938, 196-229. Also cited by, S. Qalb-iAbid, Muslin Politic, in the Punjab, 204.

31 Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 116-117.

32 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 71.

33 Punjab Government Gazette, 5th October 1940. Also cited by Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 117-118.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Raghuvendra Tanwar, Politics of Sharing Power, 117-118.

38 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 71.

39 Ibid., 72. Also see, Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 83-84.

40 Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 84.

41 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 72.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid. Also see, Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 119.

44 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 72.

45 Ibid., 72. Also see, Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 119.

46 See Satya M. Rai, Legislative Politics and the Freedom Struggle in the Punjab, 1897- 1947 (New Delhi: 1894). Also see Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 119-120. For details see Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 72. For more detail, see David Gilmartin, Empire and Islam, 150. Mohinder Sing, History and Culture of Punjab, 207.

47 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 72.

48 Ibid. For details see Civil & Military Gazette, Lahore, 6th September, 1938.

49 But the Akali Sikh political parties encouraged arguments between the ruling Unionist Party to reassert its political influence in the Punjab. For details see, Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 72.

50 Chhotu Ram was personally hurt by the attitude of Moneylenders. Mian Abdul Haye had been an important minister in the Punjab Cabinet not only with Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan but also continued with Sir Khizr Hayt Khan Tiwana. The government wanted them to get in touch with masses; it therefore highly appreciated such tours. See Agnithori and S. N. Malik, Chhotu Ram: A Prolific Courage, Delhi, 1978. Also see, (Governor to Viceroy, 24

August, 26 october 1938, L/P & J/5/240, IOR; Viceroy to Governor, 30 March 1938, Linlithgow collection, 125/86 IOR.)

51 See Civil & Military Gazette, Lahore, 12 & 13 August, 6 September, 13 & 22 October 1938.

52 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 71.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 Ibid.

56 Civil & Military Gazette, Lahore, 6th August 1938, 16 January 1939.

57 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 68. And S. Qalb-i-Abid, Muslim Politic, in the Punjab, 204-207.

58 Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, 68 & 73. And S. Qalb-i-Abid, Muslim Politic, in the Punjab, 204-207.

59 Essays, UK. (November 2013). Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan And Demand For Pakistan History Essay. Retrieved from:

https://www.uniassignment.com/essay-samples/history/sir-sikandar-hayat-khan-and-demand-for-pakistan-history-essay.php?vref=1

61 Ahmad J.-U.-D., 1941, p. 88

62 Ahmad K. 1970, pp. 45-46

63 Ideological, Cultural, Organisational and Economic Origins of Bengali Separatist Movement .

Rizwan Ullah Kokab and Mahboob Hussain.

64 1943: 204

65 Coupland, 1943: 204–5

66 1943: 204–5

67 Carter, 2004: 425–6

68 Srivastava, 2018: 232

69 Pirzada, 1995 [1962]: 179–80

70 Malik 1985: 97

71 Coupland, 1943: 239–41

72 Basu 2016

73 Khan, 2015

74 Khan, 2015

75 Khan, 2015

On 9 September 1941, Churchill stated that the Charter, in particular its third principle of self-determination, did not apply to India. In a statement to the Press in Shimla on 1 October 1942, Hyat-Khan took Churchill to task for what he described as an ‘embarrassment’: “[The] vast majority of my countrymen certainly share my belief that [the] future destiny and safety of India lie in securing [the] status of free and equal partnership in [the] British Commonwealth. I am equally confident that if the Prime Minister could see his way to make [a] fresh declaration that India shall attain that status within reasonable time after [the] War, say two or three years, all patriotic elements in [the] Country will welcome it with enthusiasm.” A few days later, the Secretary of State for India, Leopold Amery, spoke before the House of Commons in an effort to remedy the situation: I can only repeat, in order to remove any possible ground for misunderstanding, that the Prime Minister’s statement of September 9 with reference to the Atlantic Charter expressly made it clear that the Government’s previous declaration with regard to the goal of India’s attainment of free and equal partnership in the British Commonwealth and with regard to our desire to see that goal attained with the least possible delay after the War, under a Constitution framed by agreement among Indians themselves, hold good and are in no way qualified. Whether such a retraction could be fully trusted is of course a different matter, as Hyat-Khan’s above-cited comment about ‘embarrassment’ indicates.

The Partition Plan, kept secret till the time of Independence, turned into fatal error. Innocent Muslims were killed in Charhda Punjab (Eastern Punjab) whereas many innocent Sikhs and Hindus were killed in Lehnda Punjab (West Punjab). This situation was so horrible that in the month of August approx 1 million people were killed and they were mostly Punjabi.

The saddest part is that no mainstream leader, from both Pakistan or India, tried to stop the violence. Nehru visited refugee camps in Lahore. The crowd was so angered that one protesters slapped him. Neither Gandhi nor Jinnah did any constructive effort to stop violence at both ends of Punjab.1

1 Pakistan’s Forgotten Founders: A Case Study of Sikander Hyat-Khan. Jeanne M. Sheehan. Iona College, New Rochelle, USA

Witness to Life and Freedom, Roli Books, Dehli. https://www.dawn.com/news/1338270 The Dawn of Pakistan.

“The accomplishment of Unionist Party was largely the resurgence of the Agriculturist classes of the Punjab. (Under Sir Sikandar’s direction and deep interest,) Sir Chotu Ram played a very pivotal role in bringing Agrarian reforms, wide reforms to help the Agriculturists. For instance, the ‘Indebtedness Bill’ was introduced which set-up Debt Conciliation Boards in each District. The debt conciliation board function was for the petty Zamindars, small Landholders, who were not rich, so that instead of going to the Courts of Law, the Debt Conciliation Board would meet and decide on their debts. For example, if the borrower had already repaid the principal and some interest, then the debt would be liquidated or very little [additional] interest paid. This greatly helped the indebtedness of the Agriculturists that was one. The ‘Marketing Bill’ was another. All this was tooth and nail opposed by the Congress, which was largely Hindu, and some Sikhs who were not Jats, they opposed it.” 2

This government (Sir Sikandar's Unionist Government) carried out many Reforms for the better of the Punjabi Zamindar or Agrarian Community. When Indian Farmers faced a crash of Agricultural prices and economic distress in the late 1930s, Sir Sikandar took further measures to alleviate their misery in the Punjab.3

Inspired by the earlier example of his late father Nawab Muhammad Hyat-Khan, who had played an instrumental role in helping the Punjab Peasantry out of debt during the 1890s.4

According to the first-hand account of Sir Penderel Moon, who was then serving under Khan as a British ICS officer, in discussions in 1937 and 1938, Sir Sikandar explained to him the vital need for (a) maintaining the unity and integrity of the Punjab as a whole, and (b) at the same time striking a 'fine balance' in ensuring the rights of all Punjabi Communities and Communal factions; and he opined that rather than let things slide into anarchy and chaos, he would try his level best to do his 'utmost' to keep talking and making necessary concessions to all sides. While well intentioned, this was probably attempting too much in circumstances that were inevitably headed towards divisiveness and were beyond his control.5

Sir Sikander was encouraged to forge links with the Sikh leaders. In March 1942, Baldev Singh formed a new Party in the Assembly under the label of United Punjab Sikh Party, consisting initially of a few Akali and Independent Legislators. Three months later he joined the Ministry on the basis of an agreement with Sikandar Hyat-Khan. On June 15, 1942, Sikandar Hyat-Khan and Baldev Singh signed a pact known as the Sikandar-Baldev Singh Pact. Its terms, which were embodied in a letter addressed by Sir Sikandar to Baldev Singh related to ‘Jhatka’ meat, teaching of Gurmukhi, Legislation regarding Religious Matters, Sikh recruitment of Government Services and representation at the Center. The terms were so framed as to apply equally to all Communities in Punjab. But the sudden death of Sir Sikandar in 1942 changed everything in the Punjab and paved the way for the Leadership of Jinnah.

Sir Sikander tried to convince Khizr Hayat Khan to change the title of 'Unionist Government' and term his Government a 'Muslim League Coalition'. Khizr Hyat Khan refused to accept but by the time his position had changed. He was not so strong as his predecessor and now Jinnah too had emerged stronger. As a result, the number of his Muslim followers greatly decreased and he had to rely on the support of a few Unionists backed by Congressmen and Akalis. Malik Khizr Hyat Khan refused to accede to League's demands. Jinnah, in 1944, abrogated the Sikandar-Jinnah Pact and Malik Khizar Hayat Khan was expelled from the League. Jinnah apparently hoped that this would spark a large scale shift of Rural Leaders from the Unionists to the Muslim League, but it did not happen. Despite continued factional defections to the League, the Unionists enjoyed the support of the great bulk of Rural Muslim Assembly Members.

“Sikandar Hyat recognized the interest of the Muslim Community as a whole and infused new life into the Muslim League when he joined it, after he came to compromise with the Quaid-i-Azam in 1937. He also advised other Unionist members to follow him to offset “the tide of Congress totalitarianism”. Thereafter Sikandar Hyat fully supported the Quaid-i-Azam up to the last moment. On March 11, 1941 when the Quaid wanted the Muslim members of National Defense Council to resign, he not only faithfully carried out the League Mandate but also persuaded A.K. Fazl-ul-Haq to do the same. Thus the Punjab Ministry, though not the Muslim League Government, created no problems for the League during his Prime Ministership.”6

“Thanks to the Agreement reached between Jinnah and Sir Sikandar in Lucknow, the dream of Pakistan became real. All Pakistanis today should be thankful to these two great Muslim leaders and their wisdom”.7

Wolpert states that 'The Punjab was more than just a bare Muslim Majority [like Bengal]; the Punjab meant Pakistan, made Pakistan possible.”8

Our people became enemies of each other. The partition of Punjab is one of most horrible chapters of Subcontinent history.9

Ishtiaq Ahmed, in his book on Partition, “Fear of an uncertain future, lack of communication between the leaders of the estranged communities, the waning authority of the British and the consequent unreliability of the State Institutions and functionaries created the social and political milieu in which suspicion and fear proliferated, generating angst among the common people. In such situations reaction and overreaction led to intended and unintended consequences which aggravated and finally resulted in the biggest human tragedy in the history of the Indian Subcontinent.10

Sikander Hyat Khan was one of those pre Independence Political Leaders who did not consider the concept of Partition particularly the one as Muslim Majority State and the other as Hindu Majority as a good concept, “As it will only bring despair for the rest of the existing communities.” The political role played by Sikandar Hyat Khan was mainly highlighted as an opposition to Jinnah's Policy of the two-Nation Theory. This resulted in an initial conflict between Jinnah and Khan, which captured the background of League politics before independence.

“Looking at the present state of affairs in the largest province, one is reminded of an icon, Sir Sikander Hyat Khan, a good Administrator, who was the first Muslim Chief (Prime) Minister of United Punjab from 1937 to 1942, and Acting Governor for some time, goes unremembered.”

It goes to his credit that in the very first Provincial Election in Punjab under the Act of 1935, his Party secured 95 seats in a house of 175. His contribution towards the awakening of, and taking interest in the welfare, of the Muslim of the Region, cannot be forgotten. In an understanding with the Quaid-i-Azam, he allowed the Muslim Members of his Party in Punjab to join the Muslim League. The Quaid praised his Services, and called him ‘a Strong Pillar of the Muslim League’.

He was also one of the members who drafted the Original Lahore Resolution. One wonders why as a Nation we are such misers in honoring someone who in his own way contributed to ameliorating the living standard of the Muslims of a Province now part of Pakistan.

Sir Sikandar lies buried at the footsteps of the Badshahi Mosque, Lahore. To be honest, how many of us pay respect to him on his birth and death anniversary or even remember him? The media too completely ignores his achievements and makes us believe that this period was not part of our history.”11

“The tendency to narrowcast a nation’s framers is a Global Phenomenon. One of the most intriguing examples of this Global Phenomenon is found in Pakistan, where the dominant tendency has been to attribute the Nation’s founding to just one Man, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah. Undoubtedly, Jinnah is an Iconic Figure whose reputation remains unassailable. To suggest that he was the Sole Creator, however, does a disservice to both his Legacy and the Nation’s history. As important as Jinnah was, his role and contributions should not completely overshadow those of his Contemporaries.

Some scholars have set out to address this gap. Most notably, Dani12 is credited with coining the term ‘Founding Fathers of Pakistan’ (Banieen-e-Pakistan), which points to several stages in the development of Pakistan and identifies eight individuals, in addition to Jinnah, to whom he credits playing a significant role in the creation of the nation. These are all men whom Dani13 defines as ‘the real Founding Fathers of Pakistan’. It highlights particularly the contributions of the forgotten Leader Figure Sikander Hyat-Khan. The goal of broadening our collective understanding of the many, diverse voices that contributed to the founding of Pakistan is not just important for historical purposes but critical to helping understand a Nation that Scholars have long said ‘remains an enigma’14, and that, widely acknowledged more than 70 years after its founding, ‘struggles still with a coherent National identity’15.

First, a Founder is someone who should have been known and respected in their lifetime. As Gregg and Hall (2012) and Dreisbach (2012) argued, in order to be recognized as a founder, an individual has had to have been deemed worthy and recognized by his Peers.

A Founder of Pakistan must have been committed to securing Independence from Britain, an equal voice for Muslims in the Subcontinent and/ or must have worked to establish the Republic. When we apply these criteria and their lessons, we may reconceptualize the Founders of Pakistan as those Men and Women who were well known in the decades prior to and surrounding 1947 and who through their words, actions or deeds worked at minimum to secure the Independence of the five above-named Provinces from Great Britain. In addition, they may also have worked to secure an equal voice for Muslims and/ or helped to envision, design or build the new separate Democratic Islamic Republic, whether or not they were on the losing side of History in some instances. Based on the earlier definition, a number of figures from that era emerge as potential Founders of Pakistan. This includes, apart from Jinnah, the more well-known Iqbal.

Allama Sir Mohammad Iqbal.

Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan.

Aga Khan III.

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan.

But it should, as well, include those who have been forgotten in history but without whom independence and the subsequent creation of Pakistan would not have been possible, for example,

Maulana Shaukat Ali,

Madr e Millat Miss Fatima Jinnah,

Sher e Bengal A K Fazlul Haq.

and Sir Mian Mohammad Shafi.

When it comes to the latter group, no one stands out as much as the Premier of the Punjab, Sikander Hyat-Khan. The quintessential ‘Pakistan’s Forgotten Founder’ (Pakistan Ka Bhula Basra Bani) Hyat-Khan’s contributions, on each of the grounds described in the definition proffered above, are unmistakable. Hyat-Khan may have been forgotten and overshadowed by Jinnah, but notably Patrick French mentions Hyat-Khan on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Pakistan’s independence. In a review of Ahmed (1997), titled ‘Father of His Nation’ and published in The Sunday

Times of 8 October 1997, French argues that ‘Jinnah is the most undervalued world statesman of the 20th century’. But he also picks up that Hyat-Khan was not at all unimportant when he observes: ‘Yet as leader of the powerful Unionist party of the Punjab he was for a decade India’s most powerful Muslim politician’. However, due to a variety of factors, including his untimely death, the fact that he left only a minimal paper trail, and that he was critical of a Two-State solution, Hyat-Khan was largely and unfortunately forgotten by historians.

Equal Voice in the Founding of Pakistan.

In addition to working towards securing Independence, Hyat-Khan, himself a devout Muslim, also worked to ensure an equal voice for Muslims and played a substantive role in founding the new Nation of Pakistan. This is seen most clearly in the pact which he signed with Jinnah at Lucknow and the fact that he authored the first draft of the Lahore Resolution.

While Hyat-Khan supported what he described as the ‘League Resolution’, in large part because he was committed to Muslim solidarity, he continued to have reservations about it for three reasons. First, at the time, the idea of Pakistan was still ill-defined and under-conceived. As a pragmatist, Hyat-Khan was concerned about the absence of any discussion on Self-Governance, the fact that the new Nation would lack the Economic Prowess, Military Might or Infrastructure to survive and in particular the rushed nature of Partition being considered at the time. Second, as a Punjabi, he understood that Partition would result in the division of the Province he was sworn to Govern and Protect. This fear, of course, was realized shortly after his passing. Third, given his commitment to work towards the general

good, he opposed a Two-State solution on the ground that it would result in carnage of unprecedented proportions. Sir Penderel Moon (1961: 20) wrote that in a conversation he had with Hyat-Khan in October 1938, the Premier noted that ‘Pakistan would mean a Massacre’. Hyat-Khan reiterated this in a further statement before the Punjab Legislative Assembly on 11 March 1941:

“We want freedom for our Country, freedom in the sense that we shall have full control of our own affairs…We do not ask for freedom that there may be Muslim Raj here and Hindu Raj elsewhere… we should examine this problem not from any petty communal or sectarian point of view… Whatever our differences… Let us strive togeth’er for a freedom which will ensure liberty and freedom for all and which will enable us to live together.”

Once again, sadly, on this point, he was prescient as well. Partition resulted in the largest and deadliest forced migration in history, with the displacement of over 14 million and the death of more than a million people, a traumatic episode whose multiple implications still reverberate.16

Many highly respected Leaders at the time, like Hyat-Khan, urged a more cautious, moderate path based on an understanding of age-old British-Indian ties, Government, Administration, Customs, Currency, Foreign Affairs, Communications, Internal and External Security and, most of all, Hyat-Khan’s impassioned belief that a hurried, ill-conceived and unplanned Partition would result in a Massacre of unprecedented proportions. Unfortunately, he was proved right.

It is often said that history is written by the winners; thus, founders like Hyat-Khan have, far too long, been neglected. As this case study demonstrates, this is unfortunate because it robs us of the words, deeds and vision of individuals who not only played a key role in the creation of the Nation but whose example and thought are instructive today.”17

“The

issue of Pakistan could not be ignored in the

Punjab,

where Jinnah had a strong foothold, as the major area was Muslim

dominant, and the Sikhs only formed a minority. As Jinnah promised to

look after

the welfare of the Minority,

this appeased the drifting relationship between Jinnah and Sikandar

Hyat. The Lahore Resolution

included the

assurance that

adequate, effective and mandatory safeguards will be provided to the

Minorities,

to protect their Political,

Cultural,

Religious,

Economic,

Administrative

and other rights and will express interest in discussing these

matters with

them which will be considered adequate and effective to express the

views of the Minorities

of the area.

With

the passing

of the

Lahore

Resolution,

Jinnah made all efforts to avoid any clash between the Muslim

Government and Muslim led Party,

ensuring the security of the Minorities in the area. This improved

his relationship with the other leaders including Sikandar Hyat Khan

who was now indebted to Jinnah for continuing discussions on the

issue of Partition.18

The Lahore Resolution was originally drafted by Sikandar Hyat Khan, the Unionist Leader (who was also President of the Punjab Muslim League by virtue of the Sikandar – Jinnah Pact of Lucknow).19

“The conditions of Indian Muslims is quite otherwise. Over 90 million in number, they are in quantity and quality a sufficiently important element in Indian life to Influence decisively all questions of Administration and Policy. Nature has further helped them by concentrating them in certain areas. In the Hindustan State there will remain three and a half Crores of Muslims scattered in small minorities all over the Land. With 17 per cent in U.P, 12 per cent in Bihar and 9 per cent in Madras, they will be weaker than they are today in the Hindu Majority Provinces. They have had their homelands in these regions for almost a thousand years and built up well known centers of Muslim Culture and Civilization there. They will awaken overnight and discover that they have become alien and foreigners. Backward Industrially, Educationally and Economically, they will be left to the mercies to what would become an unadulterated Hindu Raj.”20

In 1937, Sikandar Hyat-Khan signed the famous Sikandar-Jinnah Pact at Lucknow, which led to the Lahore Resolution of 1940, calling for an autonomous or semi-independent Muslim majority region within the larger Indian confederation-- which demand, later after his death, led to the demand for an independent Pakistan. In his lifetime, he controlled the Punjab Muslim League too, and with his sagacity, saw that this move of reconciling Muslim interests with Indian and Punjabi unity was paramount.21

A fallacy has been perpetuated upon history. The pro Muslim League writers insist that the Sikandar-Jinnah Pact was an instrument that was forced by circumstance upon the Unionists due to the competition with the Congress and the need for ML support. This is simply not true. These writers admit that the ML was non existent in the Punjab so what support was needed? Secondly the stance of Sir Sikandar is very clear as a dedicated and devout Muslim he supported the ML on the All India level but kept them out of the Punjab due to the difficult job of running the Province through a Coalition of Hindhu and Sikh Parties even when their support was not needed to form the Government. Sir Sikandar was a Statesman and did not want communal disharmony to wreck the peace in the Punjab. His 7 Zone scheme was intended to preserve the unity of India while ensuring protection to the minorities, especially the Muslims.

Sir Sikandar Hyat-Khan’s, “Chief Minister of Punjab Province Scheme of Indian Federation,” ‘Outlines of a Scheme of Indian Federation.’ which he made public in1939, depicted his future vision. In this scheme, he proposed the creation of ―an All-India Federation on Regional basis, which was to be demarcated into Seven Zones, having loose Federating Units.22 The Punjab was in Zone Seven, which included Punjab, Sind, NWFP, Kashmir, Punjab States, Baluchistan, Bikaner and Jaisalmir. It was proposed that India attain Dominion Status, as in Canada and Australia. Each Zone would have it’s own Legislature and the Representatives of the various Regional Legislatures were to constitute the Federal Assembly. This scheme proposed for the loosest of Federations, with Regional or Zonal Legislatures, dealing with common interests. He suggested enormous powers for the Provinces and minimum to the Central Government. The option to gain Independence after a few years, in case the Scheme did not function as envisaged, was a move to ensure peaceful transfer of allegiance with minimal disruption in daily affairs and certainly avoid Communal Strife. The Zonal Scheme was not a Declaration of Secession from India, but it certainly was an important Milestone, as the most prominent Muslim Leader of the most important Muslim Majority Province of India – the Punjab, propounded it.

A Sub Committee was appointed by the Working Committee of the AIML on March 26, 1939, to achieve consensus on various Schemes of Partition of India already propounded.

The Lahore Resolution was interpreted by Mohammad Ali Jinnah and by Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan in different ways. The former was clear in his mind that the League Resolution implied the establishment of a separate State or States; while Sir Sikandar interpreted it as meaning no more than the concession of maximum Autonomy to Regions in which the Muslims formed a Majority of the Population. Informal efforts were made in private for a settlement between the Congress and a section of the Muslim League led by Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan.

This was enough to show Sir Sikandar's resistance to the Lahore Resolution. He further said, "If Pakistan meant unalloyed Muslim Raj, he would have nothing to do with it", and 'what he wanted was a Raj, in which every Community would be a Partner'. Sir Sikandar Hyat-Khan himself wanted the Central Government to deal with matters of such outstanding importance as Customs, Communication and Defense, without which he said, “Indian Independence would be short lived”. The prospect of separation from the rest of India would give the Federal Constitution the weakest possible start. The threat of possible separation would be a sort of ‘Damocles's sword perpetually hanging over the hands of the Federal Authority’; which could not but interfere at once with its strength and efficiency and obstruct its smooth working.

Although Sikandar Hyat’s Zonal Scheme was not ‘Communal’ in the strict sense of the word yet its close resemblance to Iqbal’s ideas and Chaudhary Rahmat Ali’s Pakistan Scheme could not be missed. Sikandar Hyat, as a Member of the League Working Committee, was certainly the guiding force behind the Proposals for reviewing the 1935 Act. However the suggestion for re-organizing the Indian Federation with greater Provincial Autonomy was bound to be used in a different manner by the Muslim Nationalists.

Sikandar Hyat urged Jinnah to adopt a ―constructive approach in early 1940. Obviously, he realized that the plans for having maximum Autonomy could not be materialized unless a concrete scheme is given by the League. Thus, in a confidential telegram to Sikandar Hyat, Liaquat Ali Khan tried to allay his fears. The telegram apart from asserting that Muslims are a ―Nation and ―not a Minority in the ordinary sense of the word also stated: ―Those Zones which are composed of Majority of Mussalmans in the Physical Map of India, should be constituted into Independent Dominions in direct relationship with Great Britain. Ikram Ali Malik, in his book, has published a preliminary draft of the 1940 Resolution, which he opines was presented by Sikandar Hyat-Khan as it closely resembles his Zonal scheme. The preliminary draft, apart from stating that the Constitutional plan be recognized as de novo (Anew), warned that no new Plan will be acceptable unless ―the Units are completely Autonomous and Sovereign. The Document noted: Contiguous Units are demarcated into Regions which will be so constituted that Provinces in which the Muslims are numerically in majority, as in the North-Western and Eastern zones of India, are grouped in Regions, in such a manner as not to reduce the Muslims to a state of Equality or Minority therein. In addition, the Draft also envisioned giving Residuary Powers to the Units. But Sikandar Hyat’s inspiration came not from the new ideas of Muslim Nationhood which had gripped the Punjab. He was still talking in terms of a Non-Communal and an Autonomous Punjab. For instance, while explaining the Lahore Resolution he said: “If you want real Freedom for the Punjab that is to say a Punjab in which every Community will have its due share in the Economic and Administrative fields as Partners in a common, then that Punjab will not be Pakistan, but Punjab, Land of Five Rivers.”